Ethereum is a blockchain with a built-in Turing-complete programming language. It allows anyone to create a decentralised application, by making use of Ethereum smart contracts.

“The Ethereum Virtual Machine (EVM) is the part of Ethereum that handles smart contract deployment and execution” (Antonopoulos and Wood, 2018).

The EVM consists of a stack-based architecture. In order for a smart contract to be deployed, all high level Ethereum smart contract code must first be compiled into machine-readable code (called bytecode). This bytecode code (a series of single-byte opcodes and optional arguments) is then processed by the EVM via a last-in-first-out stack arrangement. This operation is similar to the Java Virtual Machine (JVM) whereby every instruction begins with a single-byte opcode and arguments, if any, occupy subsequent (unaligned) bytes, with values given in big-endian order (Scott, 2009).

The first goal of this article is to explain the inner workings of Ethereum’s stack-based EVM. Once these EVM fundamentals are explained we will begin to see that Ethereum’s organic conformity to the binary instruction format for a stack-based virtual machine has it poised to transition into the bright future of web assembly.

Let’s start with the end in mind by taking a look at web assembly.

Web Assembly (abbreviated Wasm)

WebAssembly (abbreviated Wasm) is a new type of code that can be run in modern web browsers. It provides new features and major gains in performance. Wasm is designed to be an effective compilation target for low-level source languages like C, C++ and Rust etc (MDN Web Docs, 2019).

Ethereum Web Assembly (abbreviated Ewasm)

Ethereum Web Assembly (abbreviated Ewasm) is a deterministic smart contract execution engine built on the modern, standard WebAssembly virtual machine. Ewasm is the primary candidate to replace the EVM as part of the Ethereum 2.0 “Serenity” roadmap. Ewasm is also proposed for adoption on the Ethereum mainnet (ewasm, 2019).

Why Ewasm?

The current architecture of the EVM is one of the greatest blockers to raw performance (GitHub EIP48, 2019). For example, whilst the 256-bit word size facilitates native hashing and elliptic curve operations (Antonopoulos and Wood, 2018), it also makes translation from EVM opcodes to hardware instructions more difficult than needed; an architecture that provides a closer mapping to hardware will considerably enhance Ethereum’s performance (GitHub EIP48, 2019).

Aside from the performance enhancement aspect, one of the design goals of the Ewasm project is to also support smart contract development across a wider range of languages and tooling i.e. incorporating LLVM, C, C++, Rust, JavaScript into the development cycle. In theory any language, that can be compiled to Wasm, can be used to write a smart contract. As long as it implements the Ewasm Contract Interface(ECI) and Ethereum Environment Interface(EEI) (ewasm, 2019).

Smart Contracts

Let’s take a minute to understand the fundamentals of the EVM by walking through the creation, compilation and deployment of an Ethereum smart contract, using the original EVM architecture.

Ethereum smart contracts are like “autonomous agents” that live inside of the Ethereum execution environment, always executing a specific piece of code when “poked” by a message or transaction, and having direct control over their own ether balance and their own key/value store to keep track of persistent variables (Buterin, 2013).

Each of the higher level smart contract source programming languages such as Solidity, Vyper and Lity maintain their own compiler. A smart contract’s source code can be compiled into a variety of outputs. Including, but not limited to the application binary interface (ABI), bytecode stream and opcode.

Compiling

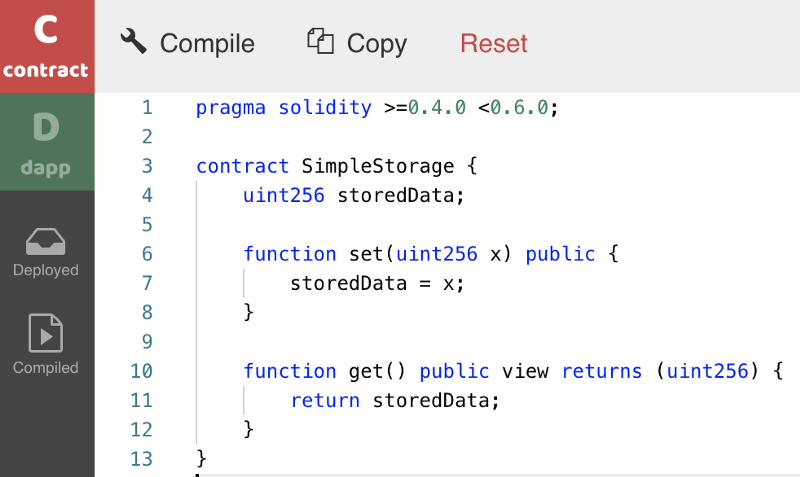

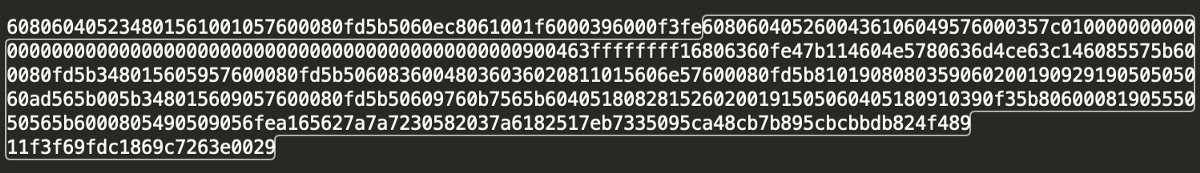

Before installing a compiler on your local machine, I would urge you to check out new web-based compilers such as SecondState’s BUIDL environment. This will save you an incredible amount of time.

Let’s take the simple storage source code and compile it using SecondState’s BUIDL environment, as pictured below.

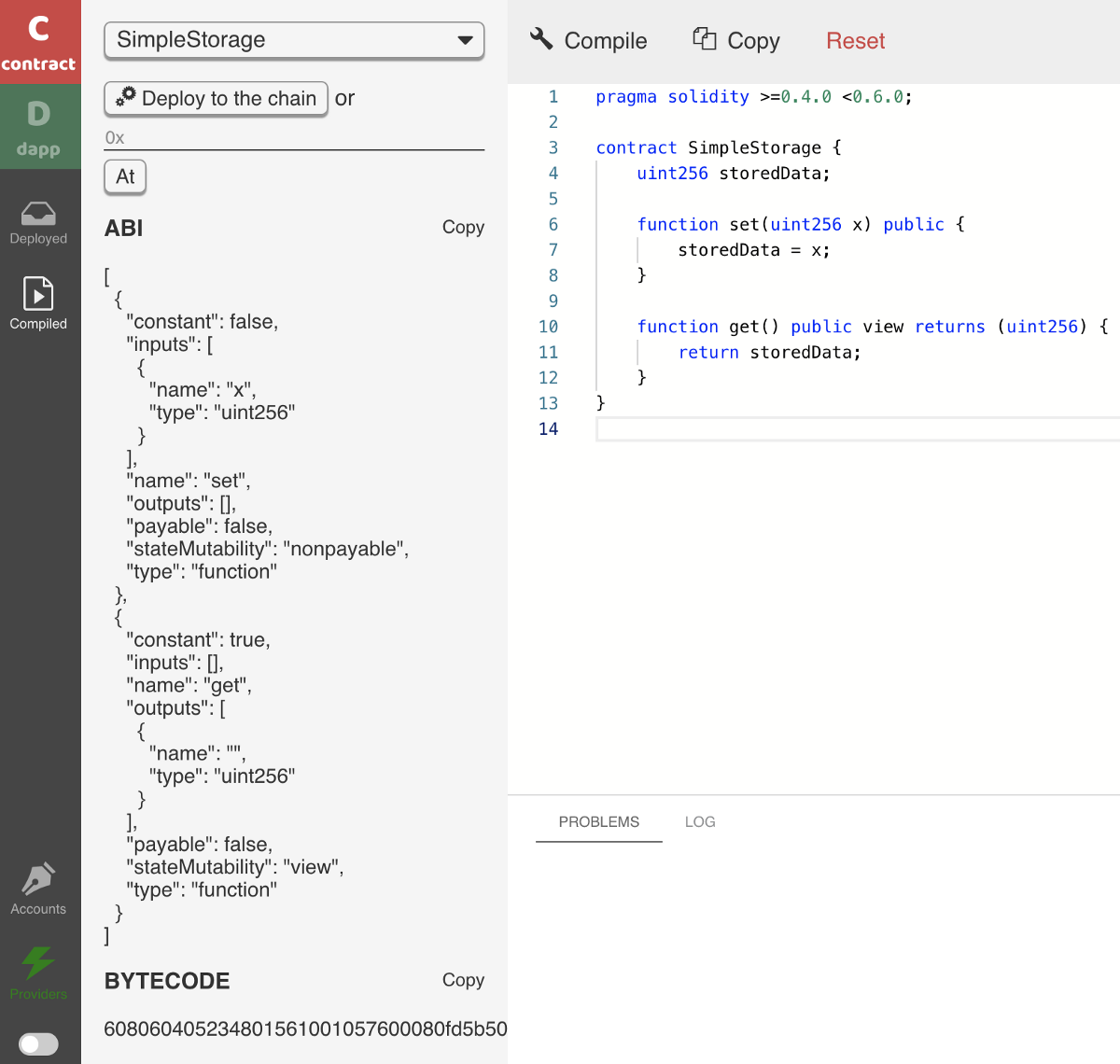

Clicking the compile button will immediately produce the smart contract’s ABI and bytecode, as shown below.

If you would like to see how this compilation is performed in the command line (with a locally installed compiler), please see Appendix A, at the end of this article.

Analysing the deployment bytecode

If we look at the first 4 instructions in the bytecode we see the following.

608060405234

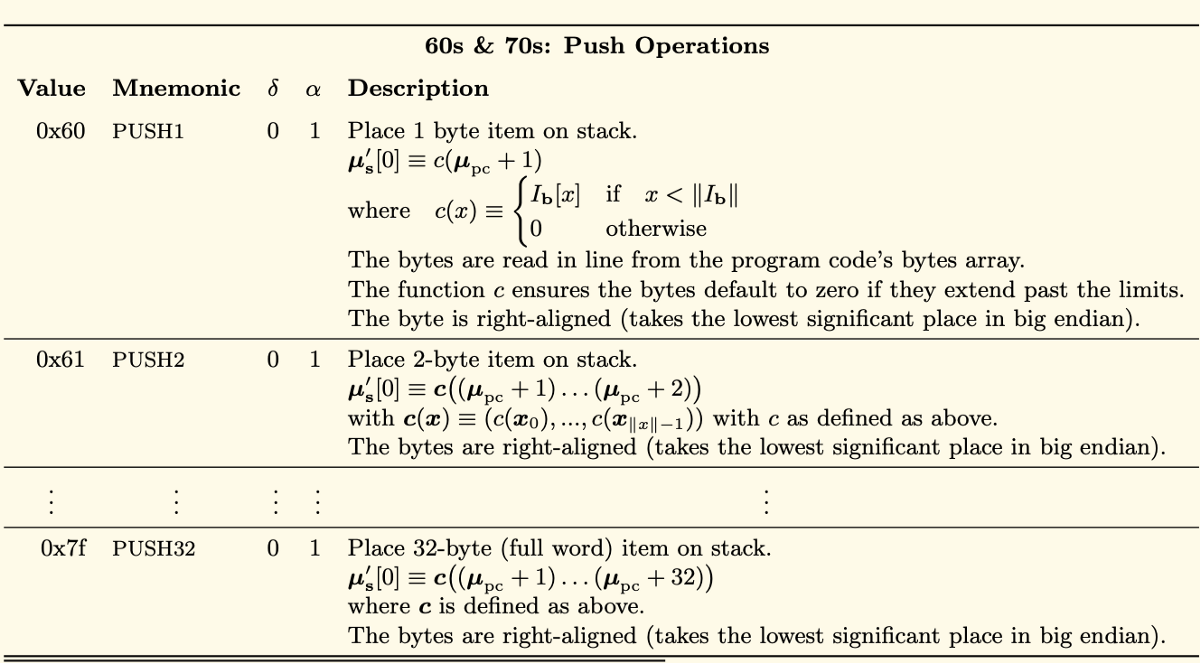

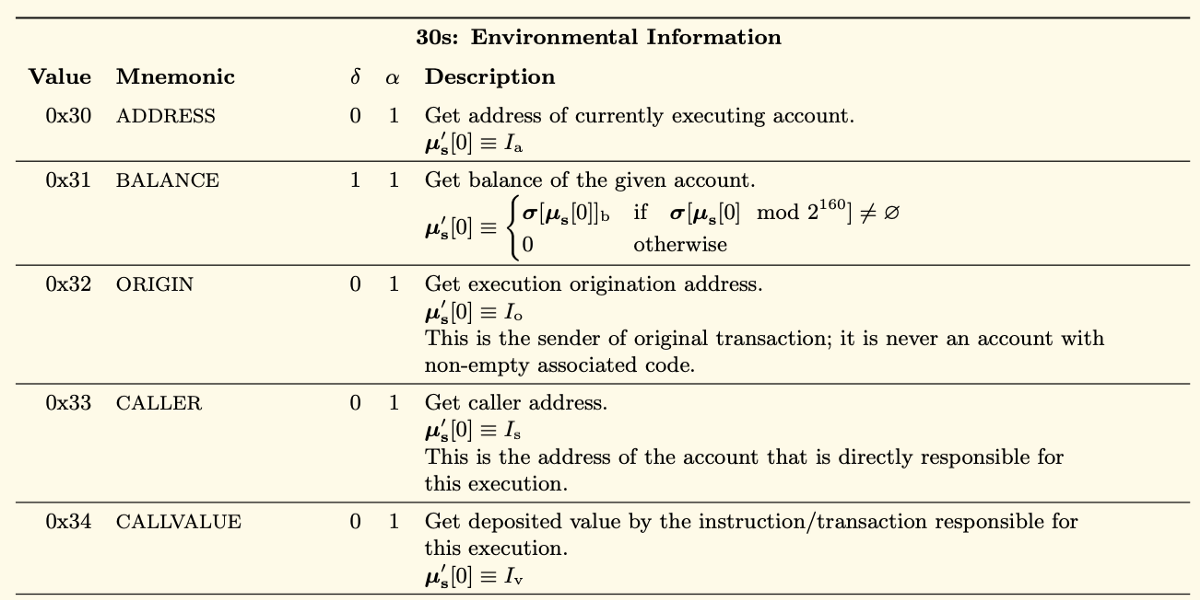

If we view the Mnemonic representations of these values, as referenced on page 30 of the Ethereum Yellow Paper, we will see that the first instruction (60) is PUSH1.

δ

The column labelled δ to the right of Mnemonic, represents the number of items to be removed from the stack by the PUSH1 instruction (in this case 0).

α

The next column over, labelled α, represents the number of additional items to be placed on the stack, by the PUSH1 instruction. In this case 1; a single byte 0x80.

In the example below we can now see that the first instruction (0x60) PUSH1, has pushed the value of 0x80 to the stack and that the second instruction (0x60) called PUSH1, has pushed the value of 0x40 to the stack.

60806040…

PUSH1 0x80 PUSH1 0x40…

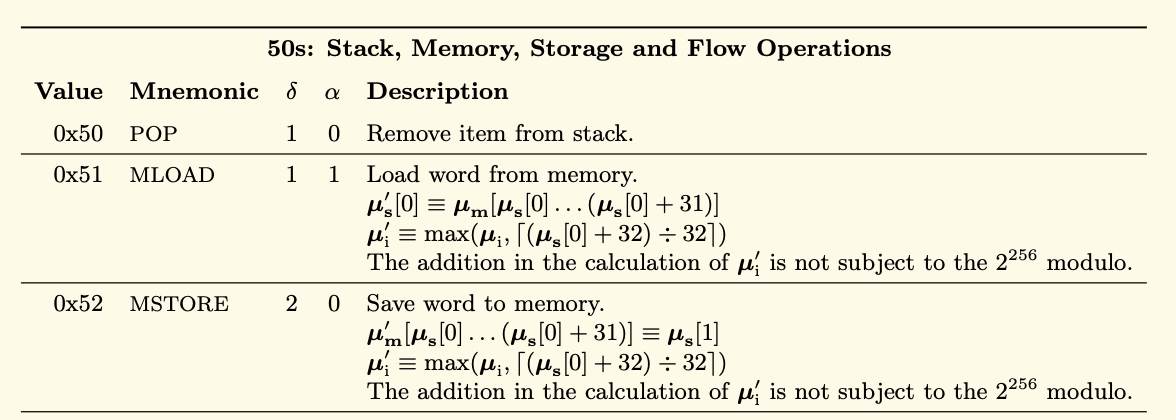

If we move along the bytecode, we then encounter the instruction with a value of 0x52. As you can see in the Yellow Paper below, this instruction has the Mnemonic representation of MSTORE.

608060405234

If we again look at the column labelled δ to the right of Mnemonic we can see that MSTORE is going to consume two items from the top of the stack. In total, MSTORE will consume the top 2 items from the stack but place 0 items back on the stack.

It is important to point out, at this stage, that MSTORE is a Memory Operation which is tasked with saving a word to memory. Please don’t get confused about the use of the term “word”.

The EVM works with a word size of 256 bit (Antonopoulos and Wood, 2018).

This “word” is not a word per se. For example, it can be an account address etc.

MSTORE starts its operation by first consuming the current item from the top of the stack; namely an address which specifies where the word will be stored in memory. In this case the address location of 0x60. MSTORE then consumes the next item from the stack and saves it (0x80) to the pre-specified address(0x60). At this stage there are no items left on the stack.

The next instruction is (0x34). It has the Mnemonic representation of CALLVALUE.

608060405234

If we pay close attention to the column labelled α, we see that CALLVALUE will be placing one item on the stack, as part of its standard operation. However, we did just mentioned that the stack is currently empty and so this raises the following question. How does CALLVALUE obtain the data which it intends to place on the stack?

As you can see from the Yellow Paper, all instructions which have values in the 30s (0x30 to 0x3e) relate to Environmental Information. In this case CALLVALUE obtains its required data from the message call responsible for executing this bytecode. Another example relating to Environmental Information is the instruction 0x33 which has the Mnemonic representation of CALLER. The CALLER instruction is able to automatically get the address of the Ethereum account which initiated the bytecode’s execution.

Deployment vs Runtime bytecode

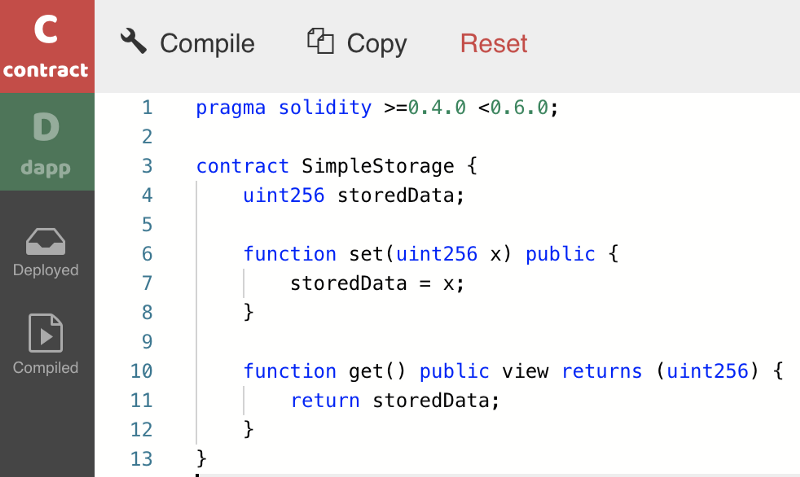

It is important to differentiate between the deployment and runtime bytecode at this juncture. If you look at Appendix A.1 (obtaining deployment bytecode) and Appendix A.2 (obtaining runtime bytecode) you will notice that the bytecode results, which are returned, are not identical.

The runtime bytecode is the bytecode that is executed when functions of the deployed smart contract are called.

The deployment bytecode contains additional instructions, relating specifically to deployment only.

Interestingly, the runtime bytecode can always be seen as a subset of code, which resides verbatim inside the deployment bytecode. This is illustrated in the image below.

Analysing the runtime bytecode

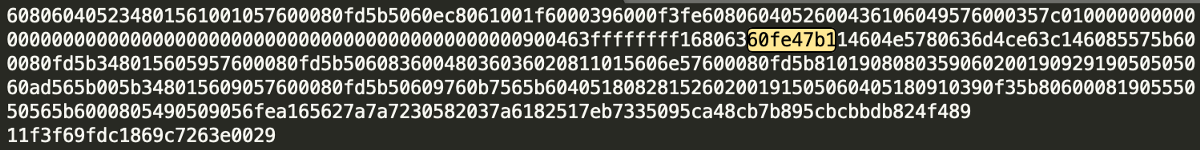

Each of the smart contract functions can be identified (inside the runtime bytecode) as a 4 byte function signature. To calculate the function signature we first take the function’s name. In our case, let’s start with our function “set”.

Along with the function name “set”, we also take the function’s input argument data types (separated by comma and wrapped in parentheses). For example, in our simple case we end up with the text set(uint256).

Note: Do not use any spaces when creating the function selector text.

Once we have this information we then create the hexadecimal representation of a sha3 hash and truncate it to only 4 bytes. Here are examples in both web3.js and web3.py

selectorHash = "0x" + str(web3.toHex(web3.sha3(text="set(uint256)")))[2:10]

var selectorHash = web3.sha3("set(uint256)").substring(0,10)

Both of the above commands will return the following signature 0x60fe47b1 which we can easily locate in both the deployment and runtime bytecode data.

At this stage we have an understanding of how each instruction in the bytecode is carried out (giving and taking information from the stack, then calling environment and memory etc). We could continue to analyse each instruction in the bytecode and reference the Yellow Paper. However, we now have a good understanding of how calling code can execute state transition functions using environmental information and so forth so let’s now move on to Ethereum’s specific Ewasm implementation nuances.

Ewasm implementation

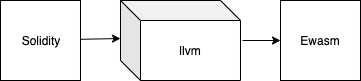

We mentioned a little while ago that a smart contract’s source code can be compiled into a variety of outputs. Of course the path from high level smart contract code to Ewasm is a complex task which can take on many and varied compilation paths through different toolchains.

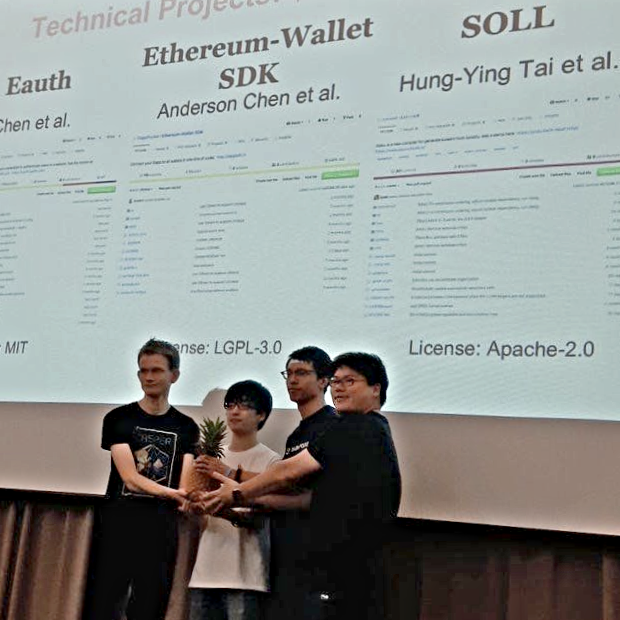

Second State developers recently built a Solidity to Ewasm compiler called Soll.

This challenging task was completed (as a prototype for demonstration purposes) prior to both:

- Crosslink - a conference for the world's leading blockchain researchers and developers, held in Taiwan's capital, Taipei)

- Devcon5- an international conference for Ethereum developers, held in Osaka Japan)

Crosslink (October 2019)

Picture: SecondState's Hung-Ying Tai receiving an Ethereum Foundation Grant for the Soll compiler project (pictured with Vitalik Buterin at the Crosslink Taipei event).

Devcon5 (October 2019)

For those who were not at Devcon5, the following video provides an overview of Soll’s operation. Namely deploying and interacting with an Ethereum ERC20 Solidity smart contract on the new Ethereum Ewasm testnet.

Devcon5 was the perfect conference to share the latest Ewasm developments from the SecondState team. After formally presenting on the first day of the conference, an additional informal and open demonstration & discussion took place.

The post-demo discussion with Solidity maintainer Christian Reitwiessner, and others, revealed SecondState’s best path forward in terms of optimal collaboration and reduction of duplication of effort amongst different developers and software projects in the future Ewasm space.

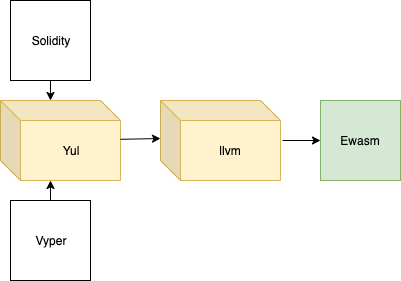

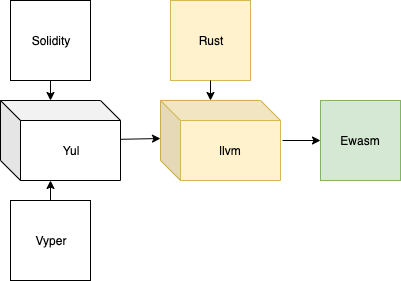

Having succeeded in prototyping compilation from Solidity to LLVM to Ewasm, SecondState, in response to valuable peer input, is looking forward to making extensive use of Yul in a bid to perform Yul to llvm to Ewasm compilation path.

Yul

Yul is an Ethereum specific intermediate language. Future versions of the Ethereum Solidity compiler (and possibly the Ethreum Vyper compiler) will comprehensively support Yul as an intermediate language.

Yul is designed to be a usable common denominator of EVM 1.0, EVM 1.5 and Ewasm. The core components of Yul are functions, blocks, variables, literals, for-loops, if-statements, switch-statements, expressions and assignments to variables (Solidity — Yul, 2019).

Backends or targets are the translators from Yul to a specific bytecode. Each of the backends can expose functions prefixed with the name of the backend. Yul reserves evm_ and ewasm_ prefixes for the two proposed backends (Solidity — Yul, 2019).

A lot of work has already been done in this space, so let’s take a brief look at what we already know about the path from Solidity to Yul to Ewasm.

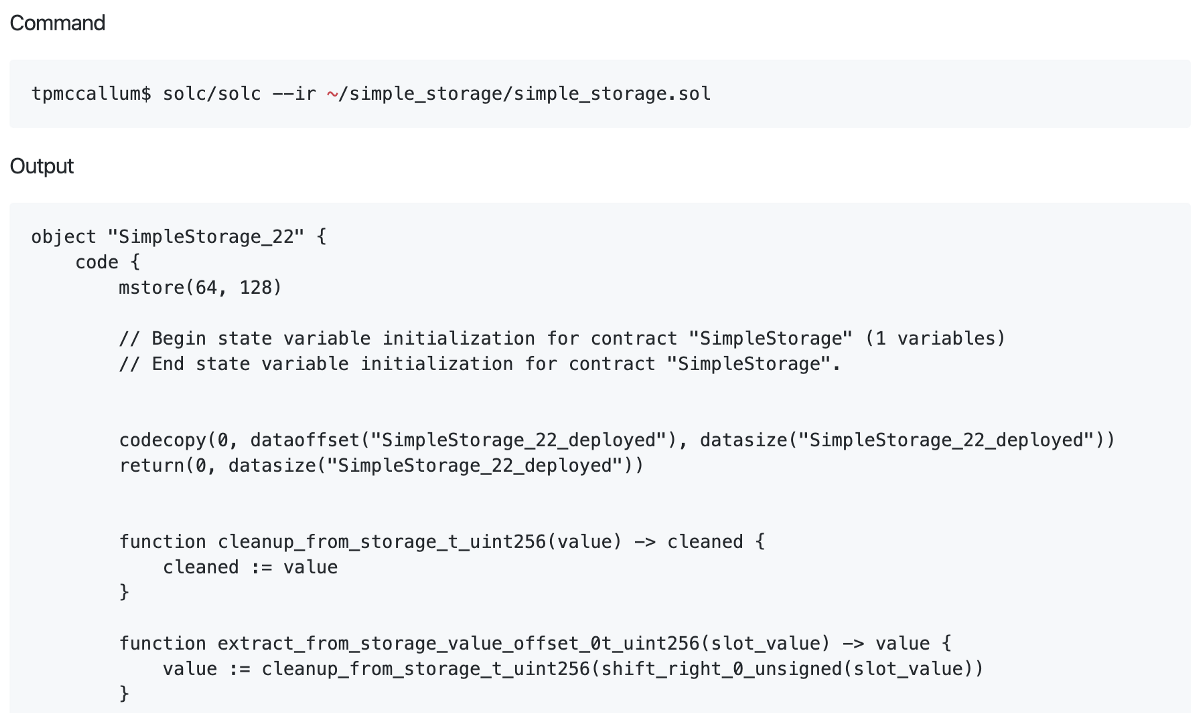

Compiling Solidity for Yul

The solidity compiler has a special flag which can be used to compile Solidity source code into an intermediate representation (IR) of Yul.

In order to provide an example of this feature, let’s use Ethereum’s Solidity compiler in the command line to compile our simple storage example from above into this YUL IR format.

You will see from the code below that we can perform this task using the ir flag.

Compiling Yul for Ewasm

A simple overview of the path from Yul includes the following steps.

Starting with the EVM-Yul code, we need to: Split each 256 bit (32 byte) variable into 4 individual 64 bit (8 byte) variablesTake care of endian differencesCreate a library that implements each EVM opcode as user a defined function, using the equivalent Ewasm built in functionUtilise the regular optimiser.

Further Solidity compilation examples

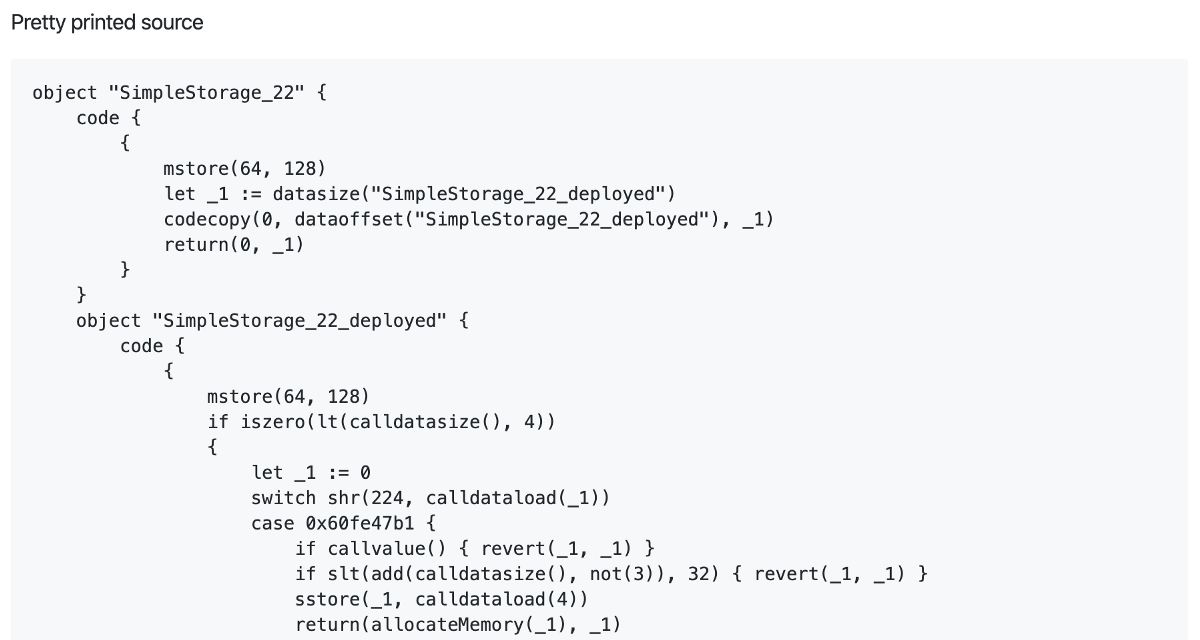

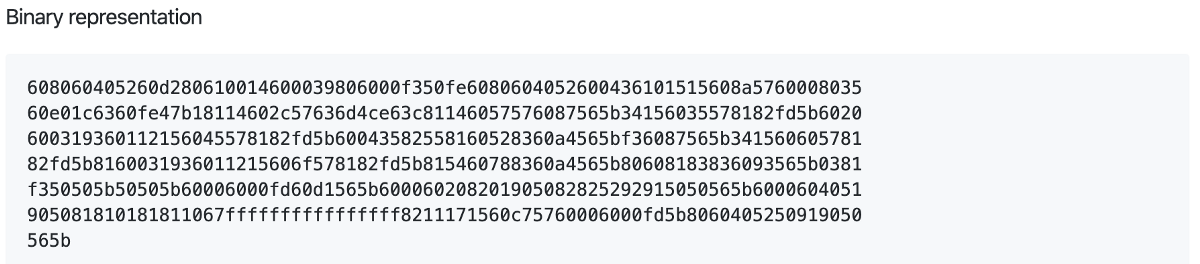

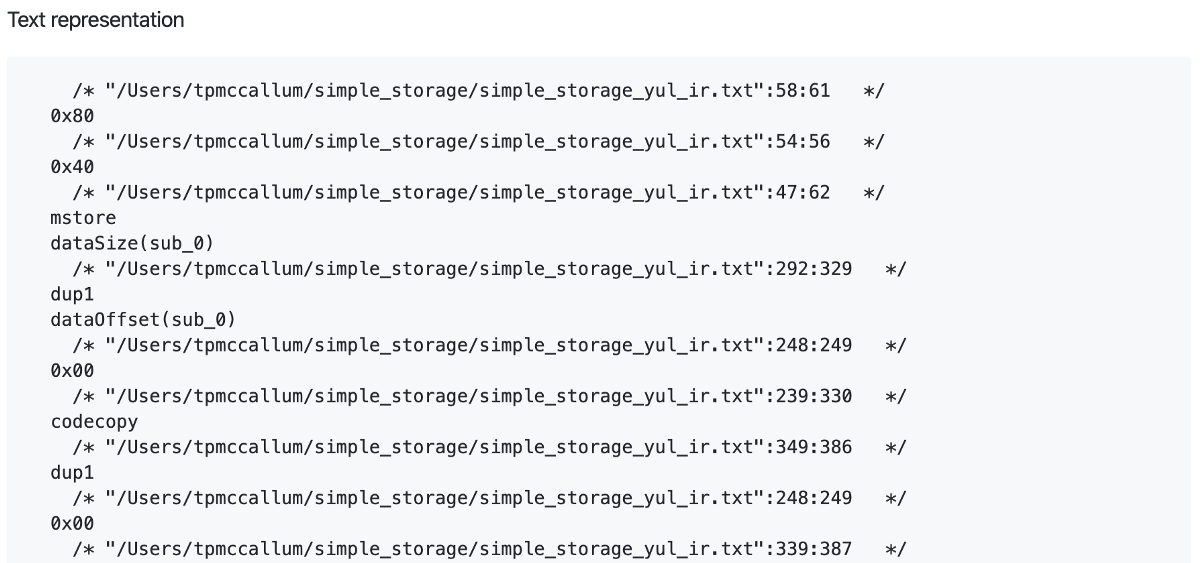

If fed the above Yul IR, Solidity can also produce pretty printed source, binary representation and text representation.

This is achieved with the following command

solc/solc --strict-assembly --optimize ~/simple_storage/simple_storage_yul_ir.txt

The individual outputs are as follows

An example of the inner workings

Christian’s Devcon5 presentation code example, revealed the inner workings of the Ewasm flavoured compilation process. More specifically, as shown here, the work required to produce the equivalent of the MSTORE function. As we demonstrated above, using the original EVM, MSTORE accepts 2 arguments (firstly a standard 32 byte address, and secondly a 256 bit (32 byte) word). However, as you can see, the code below shows the original Solidity smart contract 256 bit variables being split into separate 64 bit variables. You will also notice that endian swaps are occurring.

|

|

Available at: http://chriseth.github.io/notes/talks/yul_devcon5/#/11

Endianness

The swapping of endianness (the byte order for storing and retrieving bytes from memory) when compiling for Ewasm is crucial for the following reasons. The Ethereum Virtual Machine Specification employs big-endian byte ordering (Wood, 2014). However, the Web Assembly specification requires that all values are read and written in little endian (webassembly.github.io, 2019).

As not to undersell any of the other required design efforts and hard work ahead, there are additional details which are currently undergoing consideration/discussion as this important work progresses. A few of these have been outlined in Appendix B below for brevity.

Conclusion

Whilst there are many potential paths between smart contract code and Ewasm. The use of Yul will provide a targeted endpoint for the current Ethereum compilers as well as an entry point for the llvm to Ewasm compiler. The Yul to llvm to Ewasm compiler will bring about the fundamental advantages of Wasm/Ewasm to any of the Yul compliant smart contract languages like Solidity and Vyper.

Using Yul is a big win, because it can re-use almost all optimiser components (Reitwiessner, 2019).

Further to this, given that other languages like Rust use LLVM as their primary codegen backend (Rust-lang.github.io, 2019), the above toolchain path will open the door for other programming languages to become part of Ethereum’s Ewasm smart contract ecosystem.

CC BY 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0)

References

Antonopoulos, A. and Wood, G. (2018). Mastering Ethereum. 1st ed. O’Reilly Media.

Buterin, V., 2013. Ethereum white paper.(2013). URL https://github.com/ethereum/wiki/wiki/White-Paper.

Docs.ethhub.io. (2019). Ethereum 1.x — EthHub. [online] Available at: https://docs.ethhub.io/ethereum-roadmap/ethereum-1.x/ [Accessed 18 Oct. 2019].

Ewasm. (2019). ewasm/testnet. [online] Available at: https://github.com/ewasm/testnet [Accessed 18 Oct. 2019].

GitHub EIP48. (2019). ethereum EIP48. [online] Available at: https://github.com/ethereum/EIPs/issues/48 [Accessed 18 Oct. 2019].

MDN Web Docs. (2019). WebAssembly Concepts. [online] Available at: https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/WebAssembly/Concepts [Accessed 18 Oct. 2019].

Reitwiessner, C. (2019). Yul, eWasm, Solidity: Progress and Future Plans. Available at: http://chriseth.github.io/notes/talks/yul_devcon5/#/

Rust-lang.github.io. (2019). Updating LLVM — Guide to Rustc Development. [online] Available at: https://rust-lang.github.io/rustc-guide/codegen/updating-llvm.html [Accessed 20 Oct. 2019].

Scott, M. (2009). Programming language pragmatics. 3rd ed. Amsterdam: Elsevier/Morgan Kaufmann Pub.

Solidity — Yul. (2019). Yul — Solidity 0.5.12 documentation. [online] Available at: https://solidity.readthedocs.io/en/v0.5.12/yul.html[Accessed 19 Oct. 2019].

Webassembly.github.io. (2019). WebAssembly Specification. [online] Available at: https://webassembly.github.io/spec/core/_download/WebAssembly.pdf [Accessed 20 Oct. 2019].

Wood, G., 2014. Ethereum: A secure decentralised generalised transaction ledger. Ethereum project yellow paper, 151(2014), pp.1–32. Appendix ACompiling the simple storage smart contract in the command line

As mentioned in the above article, compilation can be performed manually in the command line. For example after installing Solidity, Vyper or Lity you will have access to the appropriate local compilation environment.

Here is an example of how we would compile the simple storage smart contract, to obtain a variety of different outputs, using SecondState’s Lity compiler.

A.1 Obtaining deployment bytecode

tpmccallum$ lityc/lityc --bin ~/simple_storage/simple_storage.sol

608060405234801561001057600080fd5b5060ec8061001f6000396000f3fe6080604052600436106049576000357c0100000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000900463ffffffff16806360fe47b114604e5780636d4ce63c146085575b600080fd5b348015605957600080fd5b50608360048036036020811015606e57600080fd5b810190808035906020019092919050505060ad565b005b348015609057600080fd5b50609760b7565b6040518082815260200191505060405180910390f35b8060008190555050565b6000805490509056fea165627a7a7230582037a6182517eb7335095ca48cb7b895cbcbbdb824f48911f3f69fdc1869c7263e0029

A.2 Obtaining runtime bytecode

tpmccallum$ lityc/lityc --bin-runtime ~/simple_storage/simple_storage.sol

6080604052600436106049576000357c0100000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000900463ffffffff16806360fe47b114604e5780636d4ce63c146085575b600080fd5b348015605957600080fd5b50608360048036036020811015606e57600080fd5b810190808035906020019092919050505060ad565b005b348015609057600080fd5b50609760b7565b6040518082815260200191505060405180910390f35b8060008190555050565b6000805490509056fea165627a7a7230582037a6182517eb7335095ca48cb7b895cbcbbdb824f48911f3f69fdc1869c7263e0029

A.3 Obtaining opcodes

tpmccallum$ lityc/lityc --opcodes ~/simple_storage/simple_storage.sol

PUSH1 0x80 PUSH1 0x40 MSTORE CALLVALUE DUP1 ISZERO PUSH2 0x10 JUMPI PUSH1 0x0 DUP1 REVERT JUMPDEST POP PUSH1 0xec DUP1 PUSH2 0x1f PUSH1 0x0 CODECOPY PUSH1 0x0 RETURN INVALID PUSH1 0x80 PUSH1 0x40 MSTORE PUSH1 0x4 CALLDATASIZE LT PUSH1 0x49 JUMPI PUSH1 0x0 CALLDATALOAD PUSH29 0x100000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000 SWAP1 DIV PUSH4 0xffffffff AND DUP1 PUSH4 0x60fe47b1 EQ PUSH1 0x4e JUMPI DUP1 PUSH4 0x6d4ce63c EQ PUSH1 0x85 JUMPI JUMPDEST PUSH1 0x0 DUP1 REVERT JUMPDEST CALLVALUE DUP1 ISZERO PUSH1 0x59 JUMPI PUSH1 0x0 DUP1 REVERT JUMPDEST POP PUSH1 0x83 PUSH1 0x4 DUP1 CALLDATASIZE SUB PUSH1 0x20 DUP2 LT ISZERO PUSH1 0x6e JUMPI PUSH1 0x0 DUP1 REVERT JUMPDEST DUP2 ADD SWAP1 DUP1 DUP1 CALLDATALOAD SWAP1 PUSH1 0x20 ADD SWAP1 SWAP3 SWAP2 SWAP1 POP POP POP PUSH1 0xad JUMP JUMPDEST STOP JUMPDEST CALLVALUE DUP1 ISZERO PUSH1 0x90 JUMPI PUSH1 0x0 DUP1 REVERT JUMPDEST POP PUSH1 0x97 PUSH1 0xb7 JUMP JUMPDEST PUSH1 0x40 MLOAD DUP1 DUP3 DUP2 MSTORE PUSH1 0x20 ADD SWAP2 POP POP PUSH1 0x40 MLOAD DUP1 SWAP2 SUB SWAP1 RETURN JUMPDEST DUP1 PUSH1 0x0 DUP2 SWAP1 SSTORE POP POP JUMP JUMPDEST PUSH1 0x0 DUP1 SLOAD SWAP1 POP SWAP1 JUMP INVALID LOG1 PUSH6 0x627a7a723058 KECCAK256 CALLDATACOPY 0xa6 XOR 0x25 OR 0xeb PUSH20 0x35095ca48cb7b895cbcbbdb824f48911f3f69fdc XOR PUSH10 0xc7263e00290000000000

A.4 Obtaining ABI

tpmccallum$ lityc/lityc --abi ~/simple_storage/simple_storage.sol

[{"constant":false,"inputs":[{"name":"x","type":"uint256"}],"name":"set","outputs":[],"payable":false,"stateMutability":"nonpayable","type":"function"},{"constant":true,"inputs":[],"name":"get","outputs":[{"name":"","type":"uint256"}],"payable":false,"stateMutability":"view","type":"function"}]

Appendix B

Topics for future consideration/discussion

Interacting with the rest of the 1.x EVM

In addition to the typical bytecode operations, i.e. stack, memory, and storage access, the original EVM also has access to account information, i.e. addresses and balances as well as block information and current gas price (Antonopoulos and Wood, 2018). Storage access is instrumental for correct operation. For example, the execution of a valid transaction begins with an irrevocable change made to the state: the nonce of the account of the sender (Wood, 2014).

The Ethereum 1.x roadmap indicates that there are unresolved questions about how Ewasm will interact with the rest of the EVM state i.e. contract storage, ether balances and so forth. One approach is to exclude Ewasm code from directly accessing EVM state, but allow it to exchange input/output when called (Docs.ethhub.io, 2019).

Deterministic behaviour

As we know, Ewasm is a subset of Wasm, and Wasm has a couple of features which are non-deterministic. As Ewasm moves forward there will need to be a way to reject any contracts which have non-deterministic features (Docs.ethhub.io, 2019). At present it appears that this can be achieved by a single sentinel contract. The sentinel is a system contract (part of the genesis or hardfork Ewasm is enabled on). The sentinel contract has a raw interface which is used for contract validation during deployment. It works by deliberately issuing an invalid operation (invoking a regular failure) when an unexpected issue occurs or deliberately issuing the revert operation if invalid input is ever detected.

Gas metering

The calculation of gas for Ewasm contract deployment and interactions requires some future work. It is presently proposed that automatic upper bound estimations are used. Static analysis can be performed on the bytecode and, for a subset of codes, the upper bounds for executed instructions (virtual gas) can also be calculated (Docs.ethhub.io, 2019).